Full size David Caron model violin for sale. Made in 2025. Features a striking, highly figured spruce top. Please contact for details and to arrange a trial.

Full size David Caron model violin for sale. Made in 2025. Features a striking, highly figured spruce top. Please contact for details and to arrange a trial.

My friend and mentor David Caron has died. It’s difficult to put into words the depth of this loss and while my heart is heavy with grief, there’s some solace in knowing that his pain and suffering are finally over.

I first met David on my birthday in 2013, a visit that would ultimately define my life when, two years later, I asked to study with him. I was very surprised when he said yes and since then have visited him and Rebecca in Taos once or twice a month – for the past nine and a half years. I remember my first visits, sitting with him and Rebecca at the dinner table after a day of work, being regaled with stories of his childhood, musicians, instruments, anything and everything else. I couldn’t fathom how I came to be so lucky, to be welcomed with such generosity by such a great violin maker into his shop and his home. What began as a mentorship grew into something much deeper. David became more than just a teacher; he and Rebecca became family.

I didn’t realize until after I met David that my first cello teacher, Ann, played a cello of his. It was an interesting and fortuitous coincidence – perhaps the universe had been weaving our fates together long before we crossed paths. By the time I started working with him, David had already been retired for nearly a decade. The death of his daughter Sandy in 2000 had affected him deeply. She had made several excellent violins and was due to inherit his vast knowledge—acquired through decades of methodical experimentation and study. He had worked with his nephew, now-famed cello maker Larry Wilke for a time, but the loss of Sandy was especially devastating, as he not only mourned the loss of a child but also an heir to his craft. Eventually I came along—an eager and devoted student. During our time together, David made several more instruments, which brought him great joy and renewed purpose, and gifted the world a few more exceptional tools for creating music.

In the last few years, as his health declined, David was no longer able to work, so I would visit just to keep him company and help around the house. After over 60 years of working with his hands, the neuropathy caused by chemotherapy was especially hard for him to bear. He often expressed how he felt useless, that storytelling was all he could still offer. I hope he knew how much those stories meant to me, that I wouldn’t trade the hundreds of hours spent listening to them for anything. I know it brought him comfort to have someone to listen.

It meant a great deal to him that I was learning everything he had to teach, and he took real pride in my work. He was more and more proud with each instrument I made. He cried a bit on hearing my last cello. His belief in me was both humbling and deeply affirming, even if I sometimes feel unworthy of it. His mentorship didn’t just shape me as a violin maker; it transformed me as a teacher. I strive to carry forward his kindness, patience, and generosity with my own students. I wish I could have asked more questions and learned even more. An innate shyness meant that I rarely said much in his presence, and over time, our relationship settled into a rhythm where he would talk and I would listen. But my companionship helped him feel connected and relevant, and our time together was a gift—both for him and for me.

David strove to live well, to be honest, fair, and kind. He looked for ways to make life meaningful, and to continually improve himself. He drew, painted, flew sailplanes, wrote poetry and prose, read widely, relished in the animals and natural beauty of his home surroundings, and took photographs. But life knocked him around quite a lot. He was familiar with deprivation, loss, and injustice. These affected him deeply, and though he could have allowed bitterness and grief to permanently overwhelm him, he instead used them as a catalyst to reinvent, explore, and contemplate. He used his innate talent for all things mechanical and working with his hands, along with his passion for creating and improving things, to fuel his pursuit of an ideal tonal and artistic aesthetic in his instruments, always striving to improve his techniques and understanding. I admired him greatly for his strength of character and lifelong pursuit of excellence. He was a genius – largely self-taught, remarkably. Others will speak further on his genius and his legacy, but I will remember him most as my friend, and the person who taught me everything I know about violins.

I saw David for the last time at my wedding, a week prior to his death. It meant everything to Alex and me – and to everyone who knew our story – that he was there. I had always imagined I would be there with him at the end, but it was not to be. I’m glad then, that our last meeting was part of such a joyful occasion.

I’ve been highly privileged throughout my life to have incredibly generous and caring mentors and friends, and I am honored to have had David as both. There are few greater things in this life than to know the love of a beautiful soul and kindred spirit. I’ll hold in my mind and heart his knowledge, his stories, and the feeling at our last meeting of his hand in mine as long as I live.

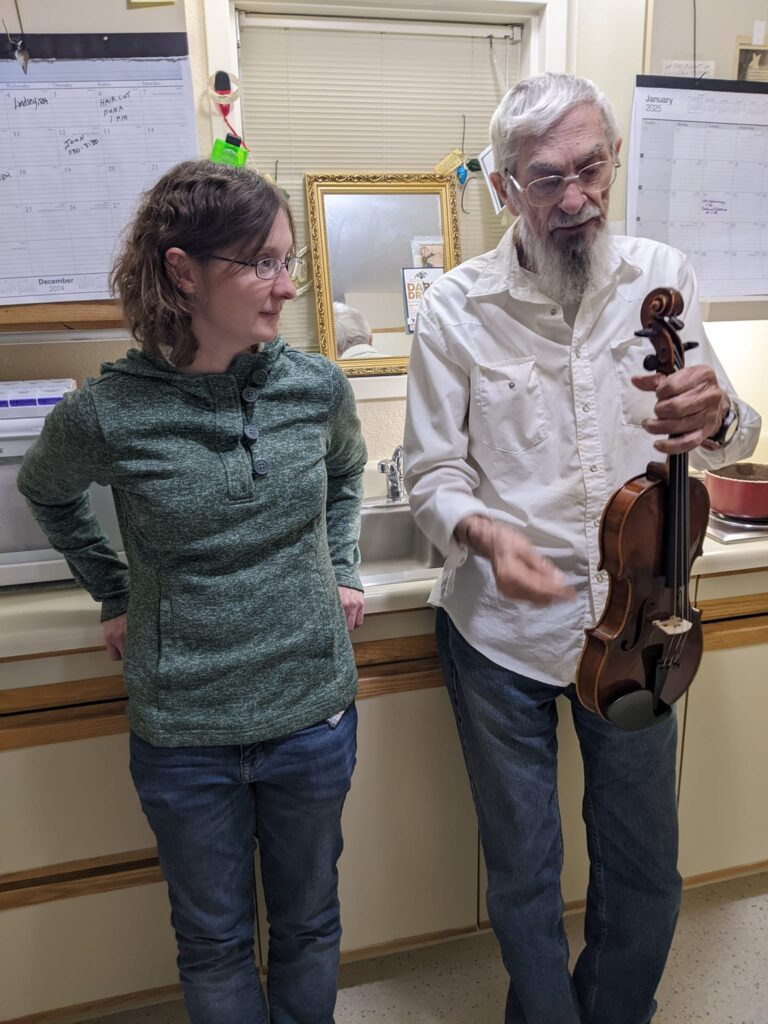

This is my friend Jim. He’s 96. I’ve only met him a few times, the first was about 9 years ago. His wife got him into making violins, which he loved, but it was too painful for him to continue once she passed away. I’ve never known anyone who loves their spouse so beautifully and so entirely. He loves to talk about his June, the most wonderful woman in the world. He alternates between giggles and tears when reminiscing about her. When he gave up violin making he wanted to give his things to someone who would use them. My name came up so he gave me a call and I drove to Cheyenne, Wyoming to meet him. On my second visit he gave me his thirteenth violin, unfinished. It’s been on my mind and on and off my bench for a good while, but I was finally able to string it up about ten days ago. Today I visited Jim to show it to him. In many ways he was the same old Jim – talkative and sweet – but there’s also some dementia setting in, so he wasn’t the same Jim I’ve visited before. He was thrilled to see me and the violin. He didn’t think he would ever see it again and never imagined it would be finished. He held and examined it in his shaking hands, tears in his eyes, and kept repeating how June would have loved it. I played him a simple tune and he told a few small stories. He was so glad to see it, and so grateful it’s finished, but never wants to see it again. It brings back too many memories of his beautiful June. I thought our visit would be longer, but he was overwhelmed, ‘the end of an era.’ This one’s for you Jim, for your June.

I have a quite a few projects in the works at the moment, including these four violins. Three are ready for polish and set-up and the other just needs a couple more coats of varnish. Stay tuned in the coming weeks for updates!

Full-size David Caron model cello available. Made in 2024. It has a slightly shorter string length of 680 mm, but the body length is unchanged. Please contact me for details and to arrange a trial.

Several years ago a friend of my mentor’s gave me ten cello-sized billets of spruce cut in Colorado. I’ve only just now gotten around to resawing it, as I’ve bought a lot of wood since then and it was taking up too much space in my wood room in its unprocessed state.

I was hoping to get more cello tops out of it, but because of twists and knots, I was only able to get three, plus twenty-nine violin/viola tops. All the waste will either be purfling practice boards for my students or firewood.

16″ David Caron model viola available. Made in 2017. Please contact me for details and to arrange a trial.

I’ve been hard at work finishing up some projects in the white and will be spending the next few months varnishing. I don’t normally work on this many instruments at once, but for various reasons they started to pile up! I have one more violin in the works and a rib structure for a small poplar viola made, but I’ll take a few weeks to catch up on some other things in the shop before resuming work on those and then starting another cello. Stay tuned for updates!

One of my David Caron model violins, played by Gabriela Fogo.

Made in 2018, this is my second 16″ David Caron model viola, played by my former violin making student Luiz Barrionuevo.